Dismantling the Colonial Archive with Annu Matthew

- Kenny Daici

- Dec 3, 2022

- 8 min read

Updated: Dec 14, 2022

Annu Palakunnathu Matthew disrupts the colonial narrative of nonwhite inferiority by applying a personal lens to untold stories through photographic and videographic methods, asserting the complexity of immigrant and Indigenous experiences around the world to reclaim erased histories.

Annu Palakunnathu Matthew is a British-born, Indian, Providence-based photographer who documents people of othered cultures through family photo albums, photography, video, audio, projections, and animations. She replaces the colonial archive encompassing European and U.S. records with more authentic and personal stories.

Matthew began photography as a way to create images using low-tech equipment, inspired by the way Indian crafts rely on simple tools. Much of her work explores her own heritage, as someone who was born and raised in Stourport-on-Severn in Worcestershire, UK, but moved to Bangalore at the age of ten and went to college in Chennai. For The Unremembered series, Matthew gathered photos of Indian World War Two soldiers from their families, both portraits and candid shots in battle. In several installations and projections, she honors their service.

Some of Matthew’s works also blend these archival images with her own photographs, such as An Indian from India, a series of self-portraits in traditional Indian clothing and jewelry that mirror the poses and captions of Native American portraits taken in the 19th and early 20th centuries. When she turns the camera onto herself, she intentionally dresses and poses in ways that reinforce Indian stereotypes of primitivity, a method that colonizers used when photographing the Indigenous people of India and the Americas.

Inspired by personal experiences, Matthew breaks the boundaries between past and present, memory and archive, and major and minor, inviting the viewer into the stories of those othered by society. I spoke with Matthew about her intentions when engaging with the audience, the processes behind her mediums, and the anticolonial ideologies that she engages with.

For your project The Unremembered, you gathered a lot of images from family photos, not from military archives, because the photos provided by the military glorified the soldiers’ struggles. When engaging with research and creating art, what other processes help you combat the colonial nature of historical documentation?

If you Google “World War II Indian soldiers,” all you see is headshots, and people outside of a military family don't really connect to those images. That's why it was important to connect with some of these families. I think an important part of pushing back against some of the colonial archive is changing some of the narrative. Hearing the personal stories and the complexity of the history, because it's not clear cut black and white as to why they're not remembered. It's also political in terms of what was going on in India at the time. You can pose some of those questions that are more gray, and allow people to consider why those stories are not included.

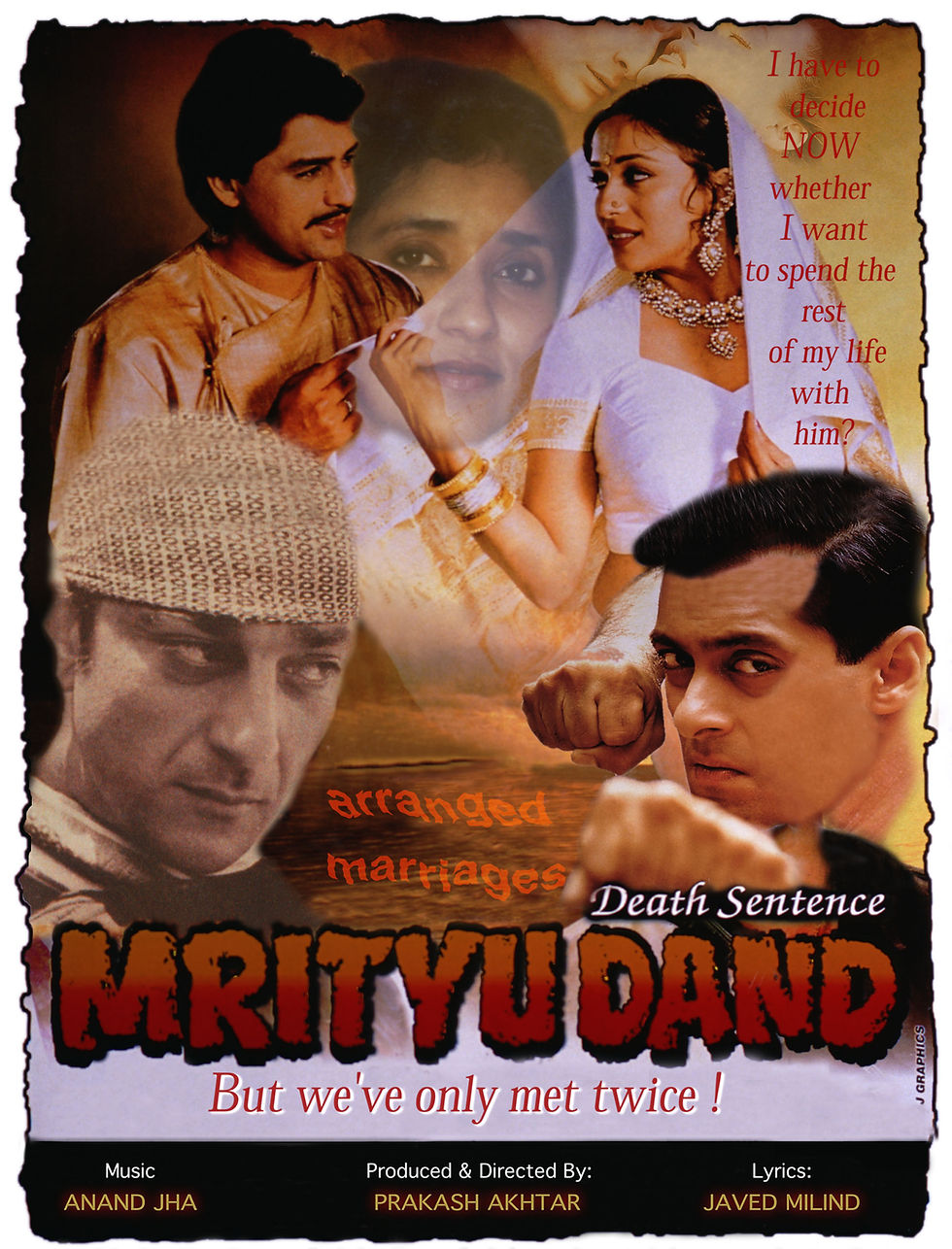

In my more feminist work, I take Bollywood posters that are very melodramatic and over the top, and I manipulate them. This was before memes were a thing. But now they're very much like memes.What I definitely try to do through that work is not only show it in galleries and museums, but also show it back on the streets of India. I've actually pasted them back onto the walls where the original posters are so everyday people who don't come to an art space actually see it. Rather than it only being about the colonial archive, it's also about making the work more accessible.

What is your intention in combining family and archival photos with your own photographs? When do you decide to use one and not the other?

I only have one body of work that is purely photographic. That's my Memories of India work, where it's trying to capture the smells and sounds that I remember of my home country. If you see my work, there's no faces, the people are silhouetted. That comes from someone who knows the culture, but also doesn't completely belong, because I was born in England. Another reason I can't be a photojournalist is not wanting to get close enough to people to photograph them. But when I started with An Indian from India, I had to do a lot of research on the history of photography, and the history of representation of both the Indigenous here, but also the Indigenous in India. There's a lot of writing about the unequal power between the photographer and the subject. Especially in those days, the subject didn't know how they were being represented. People will come and take these images, and publish them, but you'd never see that person would never see how they were being represented. And it's one of the reasons I decided to turn the camera on myself. Because I know how I'm being represented, I'm not taking advantage of somebody else. So that influenced my future projects where I wanted it to be more of a collaboration. And also a lot of the projects deal with oral histories or re-looking at history. When I go into these strangers' homes, I have a very short amount of time. So how can I break down some of the barriers for us to get talking right away? And one of those ways is opening up that photo album. It brings back memories for the families and we connect in very visceral ways. And then we agree on a photograph, which then the family collaborates with me to reenact and it becomes more of a collaboration than a one sided process of getting the information.

In To Majority Minority, you highlight stories from immigrants that are not just Indian. When engaging with other cultural communities through your art, how do you go about selecting the stories you want to share?

It’s a combination of first getting access to these families, but also trying to include a diversity of socioeconomic and education levels. So I looked at all those factors, and out of the 20 animations I show, I would have done many more, but I don't include them because I am pretty specific in terms of what I want to in the end show in terms of the larger picture. I definitely wanted families from Mexico with such a high Hispanic population in this country, and also from South America. Being an artist is not just about creating, there's a lot of research that goes into it, a lot of planning. I make a lot of lists and tick off boxes as they get filled. And if there's some that don't get filled, I have to go out and find those families, to make sure that I have tried to get the best representation that I can possibly get.

When you create works that connect other cultures to your experience as an Indian, such as An Indian from India and To Majority Minority, how do you foster empathy and acknowledging parallels between different histories while recognizing specific cultural experiences?

When I started doing the photo animation process, I didn't include any of the subjects’ stories. I started that project in India, and then I decided to expand that in Vietnam and Israel-Palestine. When I went to Vietnam, I did get access to a number of families, but I couldn't communicate with them because I wasn’t collecting stories, and I didn’t have a good translator. So that empathy didn't happen. I was initially trying to compare family photo albums across cultures, but then I realized I'm not the person to do that because I do want to have that connection with the families through their stories. In An Indian from India, I don't really deal with any live people, it was always dealing with archival work depicting Native Americans. But I have a book coming out in December where we decided to do an interview with Indigenous artists, so we could have a conversation about both the similarities and the differences between the two cultures.

An animation from "To Majority Minority" that illustrates the multiple generations of an Iranian family that immigrated to the U.S. after the Iranian Revolution

It seems that almost all of your work is related to memories. How do you decide when to use the Holga camera and when not to? What is the intentionality behind the Holga camera?

Photography is both a science and an art, if you know how exposure works. There's a technical side of photography. When I started photography, I didn't want to become a view camera, high-tech kind of person. I really wanted to be able to create images that, like a lot of Indian crafts, people use a very simple tool or a very simple stitch. I chose the Holga, which has only one shutter speed and two f-stops, and very limited focusing, because I wanted that challenge of being able to use a simple tool to create beautiful images. But also the lens lends itself to giving an image that looks like a memory because it distorts it. And there is also a certain amount of chance that happens that give you happy accidents.

In my later work, I've mainly used an Olympus camera, and that's for the reenactment of these families. But I often have to blur the image to match the original family photograph. So it doesn't really use the full potential of the camera. I use an Olympus because it's a mirrorless camera, so when I go into these families' homes, they're much less intimidated by not having a huge camera with long lenses. It's a very small body lens camera. They're more comfortable letting me photograph them. Those are the two main cameras used throughout my work.

What is the relationship between colonial archives and family memories?

About over 20 years ago. When I was right out of graduate school, I created this small handmade book called Fabricated Memories. It was to commemorate my father's 20th death anniversary. I was in England at that time for four months, so I photographed my memories of England. But when I was looking at the work, my only memories of England were about my father who died soon after we left. So I took snapshots from my own photo albums and put them back into these newly created images. I created a small handmade book that had Polaroid transfers, which was called Fabricated Memories. Now, my father has been dead for 40 years, so when the publisher sent me a copy of my book, I was stunned that she chose an image from that book that I had made for my father on the cover. She saw the thread which now I also see that my interest in memory, trauma, or untold histories, comes from my own loss and trauma from losing my father. The whole thing is intertwined.

What is your purpose in showing these pieces that are so personal?

I made that book for myself and for my family. I gave one copy to my mother and one to my brother, but it wasn't meant to be exhibited. That's such a personal experience, but apparently it connects on a larger level and curators saw it and wanted to include it in other exhibitions. But that wasn't actually the intention of the work. My husband says my work is all about me, me, me, it often starts from personal experience. But what I like to do is also make it something that is not just about me, but also larger experiences that other people can connect to. One of the bigger goals of my work is to try to shift perspectives, and especially in today's world, which is sort of divided and so black and white, I feel as if it's a way to be able to have a conversation without getting defensive. I see my work as being able to try and find that middle ground.

Comments